How Nigerian women build peace through grassroots initiatives

Oluwaseun Famoofo describes the grassroots efforts of women peacebuilders in Nigeria, who face barriers to participating in formal governance and peacemaking mechanisms.

Women suffer disproportionately from conflicts and wars around the world. They frequently witness unspeakably awful atrocities, including murders, sexual assaults, kidnapping and sexual slavery, forced marriage, and mutilations (including forced pregnancies and HIV/AIDS).

In Nigeria, women have experienced untold mental, emotional, and physical suffering as a result of the Boko Haram uprising in particular, as well as ethnic-religious disputes, and violent clashes among nomadic pastoralists and some agrarian communities.

It is crucial that peacebuilding efforts recognise the hardship experienced by women during times of conflict when creating long-lasting solutions. But it is also crucial that women are not seen only as victims. In fact, Nigerian women are actively seeking to take up leadership roles and tackle the effects and causes of protracted, violent conflict in their communities.

However, women’s participation in peacebuilding in Nigeria has unfortunately been neglected and imbalanced. This is because women have very little or no representation in government or access to formal mechanisms.

Nigerian women’s involvement in peacebuilding

In response to this struggle, Nigerian women have turned to organising grassroots efforts, forming intercommunity coalitions, and putting themselves forward as role models and mediators.

In situations where women are routinely silenced and rendered invisible in the formal, public sphere, women’s participation in Nigerian peacebuilding is frequently observed in their use of informal networks and organisations – such as loan committees, mothers’ groups, or neighbourhood alliances – to speak out about and amicably resolve conflicts, or to influence the behaviour of more formal mechanisms.

Through these grassroots efforts, women are creating systems to raise the standard of living in their communities, neighbourhoods, and families. Some focus on addressing the impact of conflict. For example, FAM – Friends Advocating for Mental Health – has been educating adolescents about mental health since 2020.

Aisha, FAM’s co-founder, said: “We are based in Zaria and Kaduna, hoping to create another branch in Abuja soon […] We create mental health-oriented clubs in schools, and we occasionally go there to talk about things like anxiety disorders, PTSD, and depression. We teach them how to look for the signs in themselves, and we also educate the teachers on how to spot these disorders in their students.”

Addressing adolescents’ mental health creates an environment for them to share their trauma and heal from it. Northern Nigeria is frequently ambushed, forcing people to live in constant anxiety. Realising this, FAM was created to help address the impact of this situation on the youth, to help them overcome this. For FAM, building young people’s mental fortitude is a way of maintaining peace in Nigeria and ensuring the youth don’t grow up vulnerable to violent extremism.

When asked about the challenges they face, she responded with, “Basically, our manpower is very low, this is volunteer work. Sometimes, people are not cooperative because of the stigma attached to mental health issues. We also have a problem with funding. Getting money to do this work is important.”

Other women-led grassroots activism focuses on the empowerment of women, such as the Feminist Coalition, co-founded by Damilola Odufuwa and Odunayo Eweniyi, which is also referred to as FemCo.

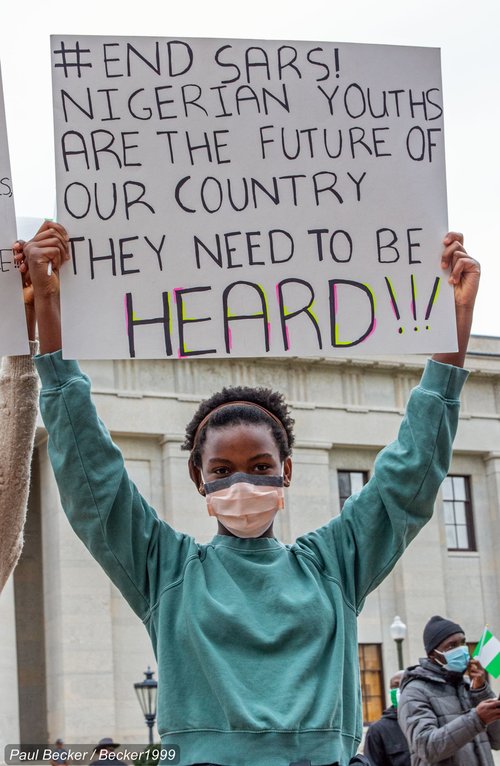

FemCo backed 183 nonviolent protests in at least 30 states of Nigeria during the #EndSARS campaign and raised money for legal and emergency services. This helped to make the grievances of the populace known to the government in a peaceful manner.

An #EndSARS protestor in 2020. Credit: Paul Becker.

The organisation’s strategy focuses on education, financial independence, and representation in public office in order to create gender equality and the empowerment of Nigerian women.

Other organisations are deeply rooted in addressing gender-based violence, such as the Stand to End Rape Initiative (STER), which was created by Oluwaseun Osowobi to fight for women’s empowerment and justice. The initiative’s inspiration came from both her own experience and the accounts of survivors that were shared with her on social media.

This organisation promotes the end of sexual violence, offers tools for prevention, and provides psychosocial help to survivors. This enterprise understands that in order for peace and development to be effective and lasting, addressing women’s and girls’ needs and demands, and supporting their involvement, are crucial.

Conclusion

Grassroots peacebuilding organisations in Nigeria are mainly dominated by women, and these women are trying their best to help one another despite barriers to broader empowerment.

Leaving the victim narrative behind, women are striving to do right by one another and spread resources to address the impact of conflict and contribute to sustainable peace.