A report by Peace Direct and Riva Kantowitz

This report is a collaboration between Peace Direct and Riva Kantowitz, an independent consultant focused on innovative and effective donor financing.

This project was designed and led by Riva Kantowitz with support from Peace Direct staff including Bridget Moix, Dylan Matthews, John Guinan, Sarah Phillips, Larisa Epafko and Eleni Kokales. The author would like to particularly thank Bridget and Dylan for their partnership in tackling a big global challenge and the project participants for sharing their candid observations and wealth of experience.

A number of reviewers whose input was critical to shaping the ideas presented here also merit thanks, including Madeline Rose, Zachary Metz, Daniel King, Syma Mirza, Kate Lapham, David Sasaki, Bob Berg and Neil Jarmon. We are grateful to Ken Barlow for editorial support, Joel Gabri for designing the online global consultation and to Inga Ingulfsen and Rosemary Forest for helping to facilitate the consultation.

This interactive site was built and developed by Ed Whicher with support from Sarah Phillips and Joel Gabri. The report would not have been possible without the generous financial support of Humanity United.

Read more about the author at https://www.peacedirect.org/rivakantowitz/

Contents

- - Introduction

- - The problem

- - Three concerns

- - How did we get here?

- - Why is it important to solve the challenge of funding peacebuilding – and local peacebuilders – now?

- - Why local peacebuilders?

- - Who is working on new approaches to funding local actors and what tools and strategies have they developed?

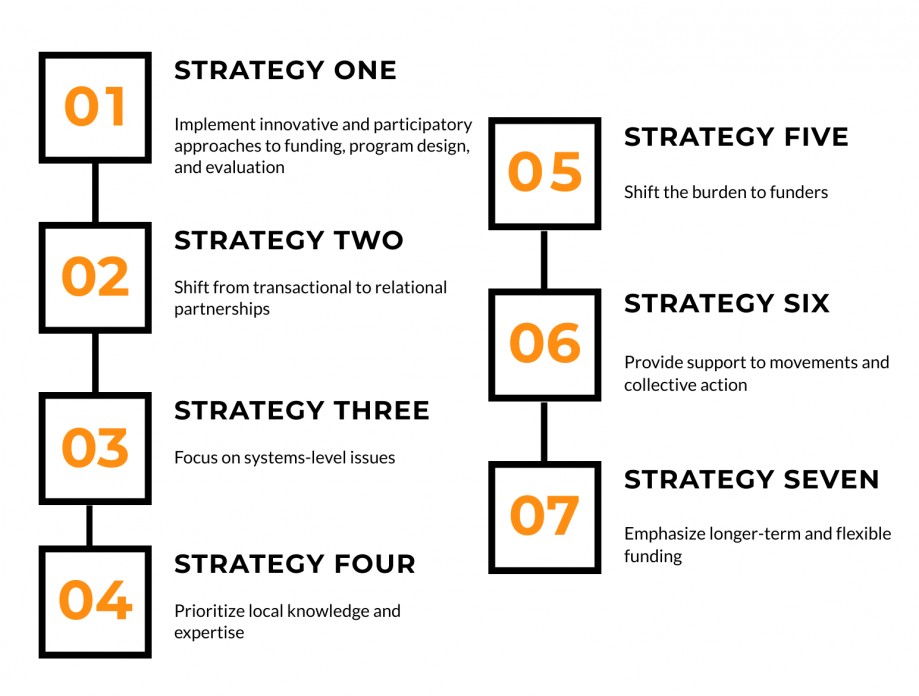

- - STRATEGY ONE: Implement innovative and participatory approaches to funding, program design, and evaluation

- - STRATEGY TWO: Shift from transactional to relational partnerships

- - STRATEGY THREE: Focus on systems-level issues

- - STRATEGY FOUR: Prioritize local knowledge and expertise

- - STRATEGY FIVE: Shift the burden to funders

- - STRATEGY SIX: Provide support to movements and collective action

- - STRATEGY SEVEN: Emphasize longer-term and flexible funding

- - Implementing the seven strategies

- - Conclusions

- - Dynamics of power

- - How do we move forward?

Executive Summary

Violent conflict is at a 30-year high. Building peace in any country requires local leadership, broad participation, and unwavering effort. Yet, the people, communities, and organizations best equipped to prevent violence and sustain peace are not receiving the recognition, respect, or resources they need from the international community. This is a situation that funders – including traditional government and private funders as well as new donors interested in social impact and solving big global problems - can and should change. Doing so offers the potential of ushering in a new era of more effective, locally led peacebuilding and conflict transformation. To achieve this, a radical reevaluation of the current system of donor funding is needed, as well as meaningful investment in new approaches supporting locally led efforts.

Peacebuilding is dedicated to resolving conflict non-violently, rebuilding lives after violence and ensuring local communities have the skills and resources to make peace a reality. This may be realized through a wide range of efforts, including directly mediating local conflicts, helping gang members and child soldiers adapt to civilian life, and empowering women in all realms, including business and politics. Despite violence prevention and resilience-building being key to any effective intervention, current funding is largely directed at reacting to, rather than preventing, conflict. Prevention or transformation includes activities that address the potential root causes of violence, such as human rights abuses, the inequitable distribution of land and other resources, and the marginalization of communities from democratic processes.

Local organizations on the frontlines of conflict are often the actors

best equipped for peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Yet, they are systematically neglected and marginalized from the

international peace and security funding ecosystem. As the Foundation Center’s – now Candid - State of Global Giving

report reveals, of the $4.1 billion that US foundations gave overseas between 2011

and 2015, just 12% went directly to local organizations based in the country

where programming occurred. Peacebuilding in general is already underfinanced,

with

private donors spending less

than 1% of the almost $26 billion in global giving on peace and security writ large, including peacebuilding and conflict

prevention. Pathways for Peace states that targeting resources toward just four countries at high risk of conflict

each year could save $34 billion in foreign aid budgets. In comparison,

spending on responses to violent conflict through peacekeeping and humanitarian

crisis response operations in 2016 was $8.2 billion and $22.1 billion,

respectively.

CHANNELS OF INTERNATIONAL GIVING DIRECT TO NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, 2011–2015

-

57.9% U.S.-BASED INTERMEDIARY

-

30.4% NON-U.S.-BASED INTERMEDIARY

-

11.7% DIRECT

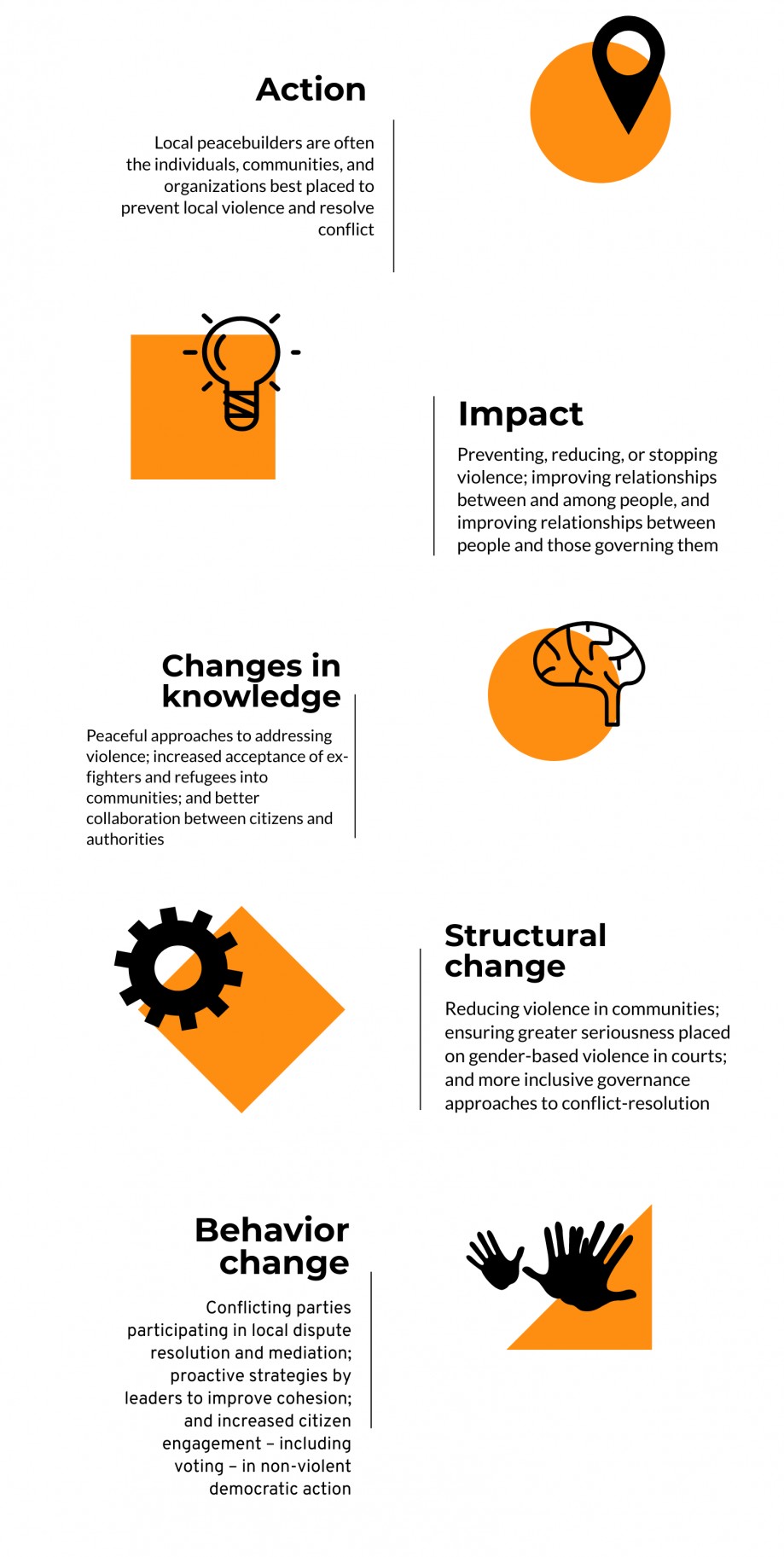

The United Nations, along with many others, has noted that successful strategies to address violence and conflict should place local actors at the forefront. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that in complex operating environments, supporting civil society to create their own solutions is often the most constructive path toward sustainable social change. A 2019 report examining more than 70 external evaluations found that local peacebuilders demonstrated significant impact in preventing, reducing or stopping violence; improving relationships among citizens (i.e. horizontal relationships); and improving relationships between citizens and those who govern them (i.e. vertical relationships).

Grants are the backbone of donor support to civil society organizations, yet they are akin to using analog technology to support social change in a digital world. In order to realize the potential of local peacebuilding work, new ways of operating outside the traditional Western grant-based donor system are needed.

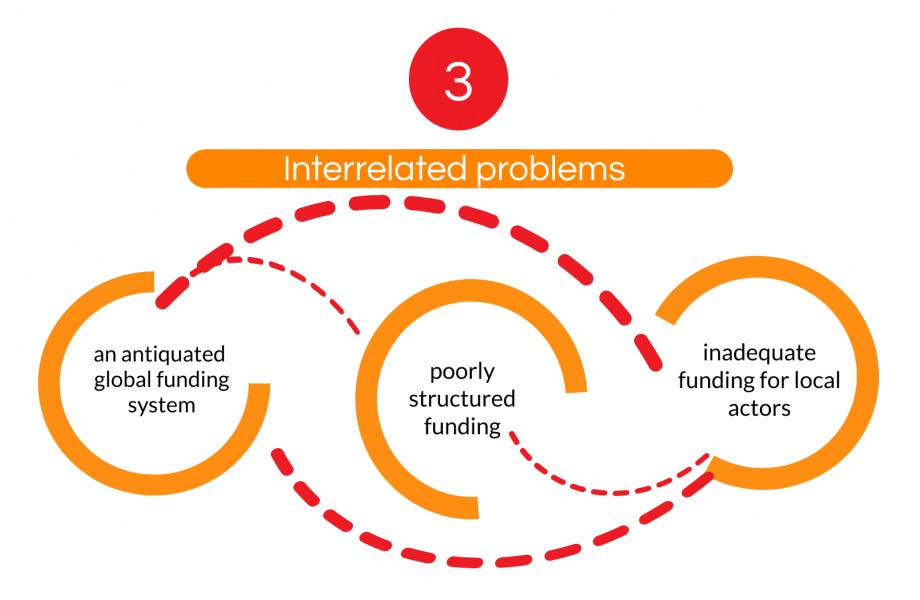

Grants are the backbone of donor support to civil society organizations, yet they are akin to using analog technology to support social change in a digital world. Grants are an outdated and ineffective tool if the funds they provide are not used with great flexibility. Indeed, this report argues that the prevailing foreign assistance paradigm has led to three interrelated problems: 1) an antiquated and calcified global funding system; 2) inadequate funding for local actors; and 3) funding that is poorly structured for the purposes of effective action and impact. In short, the current approach constitutes a bad business model. Lack of investment in local efforts undermines the billions of dollars spent on other types of intervention, creating competition instead of collaboration and forcing small organizations to waste valuable resources on constant fundraising based on immediate-term success. Through applied experience, prior research on donor financing, 25 qualitative interviews and a three-day online consultation with local actors from all over the world, this project highlights the funding approaches that hold the most promise in assisting local actors to prevent violence.

Donors utilize a range of programmatic models to effectively support local organizations, from participatory grantmaking to seeding community foundations to funding thematic or geographic ‘clusters’ of organizations and they also rely on several key strategies. The seven strategies proposed here explore: 1) promoting more participatory approaches to funding; 2) cultivating authentic partnerships; 3) encouraging funders to support improvement of systems rather than provision of services; 4) letting local partners lead while donors facilitate their work; 5) shifting administrative burdens to funders by eliminating open calls for funding, or by allowing local organizations to submit limited and/or existing organizational documents instead of creating new documents for each donor; 6) providing support to movements and collective action, including within the donor community; and 7) adopting longer-term and “radically flexible” funding approaches, such as creating flexible pots of money that can be allocated rapidly, enabling partners on the ground to change programming plans as circumstances change. Some of these approaches are relatively new (innovative finance tools, such as outcome funds and social impact bonds), others less so (participatory grantmaking, community-led financing). Irrespective of age, none of them have taken hold as standard practice. Moreover, local organizations are forced to waste resources on constant fundraising that is based on an ability to demonstrate immediate-term success. Donors must also use significant resources to monitor grants using traditional approaches and are often not reasonably able to keep up with vast piles of quarterly reports. In effect, we are using analog technology to support social change in a digital world.

This is an important set of practices; yet, it’s not enough to shift the power dynamic in the international funding industry. This report is a call to action, also outlining how a groundbreaking new fund is needed to address the lack of funding for local actors. This proposed new fund combines a number of promising approaches: community-led financing; amplifying the principals of donors that practice partnership and flexibility in grantmaking; and developing innovative finance tools to sustain peace. In doing so, it articulates which strategies are the most viable for supporting local organizations preventing violence. In practice, this means giving local organizations radically flexible tools which will enable local actors to better generate, implement, and scale their own solutions.

There is now a significant body of evidence demonstrating that community-led financing – which includes such methods as supporting community foundations – works. Community-based financing is more sustainable than traditional grant funding, as it allows communities to increase and transfer resources, or find new revenue streams. Local actors and donors who utilize what the author terms “radical flexibility” in grantmaking, including providing core support with limited administrative burdens, conclude that they get a higher return on investment. This is because organizations are neither locked into programs that are not working nor required to spend excessive time preparing supplications, fulfilling project requirements and raising money instead of implementing their to work to prevent violence and conflict. Innovative finance approaches present interesting models because they have the potential to attract new sources of funding not bound up by the old constraints. They also flip the current foreign assistance paradigm. For example, in outcome-based funding donors and investors are only concerned about whether the project achieved an agreed-upon set of objectives. In contrast, rather than depending on rigid monitoring and evaluation plans and intermediary outputs and outcomes, this model provides flexibility for local actors to shift programmatic activities as the original plans evolve and to report on them as they unfold.

In sum, this report argues for an approach to sustainable peace that inverts the current power dynamic between funders and local recipients. This will ensure greater agency and leadership at the community level, while allowing donors to play an effective and sustainable supporting role. A world with less violence is possible. The fundamental question arising, then, is how can the international community and specifically funders help? More resources for local actors is a requisite in an absolute sense; however, money is really a proxy for our values and priorities. What we really need is a movement that amplifies effective donor assistance strategies to local organizations. This movement should ensure greater agency and leadership at the community level, allowing local actors to make decisions about how to address the challenges they face in their own environments and donors to play a more impactful and sustainable supporting role. Money is one piece of that power dynamic.

-

Recommendations for governments and multilateral donors

- Invest in giving donors the capability to be more effective partners by:

• Developing long-term (ten-year) strategies that can be implemented in donor-funded one-, two-, and five-year cycles.

• Designing participatory processes that allow local stakeholders to create calls for funding, related programs and strategies for their evaluation.

• Providing flexible funding for core support when possible, and/or including emergency funds, that can be used to assist organizations in bridging gaps created by project-restricted funds.

• Exploring government capacity regarding the promotion of participatory grantmaking or providing seed funding for community foundations, as well as other efforts assisting communities generate their own assets.

- Fund the research and application of complex adaptive systems in order to help international, national, and local-level decision-makers identify intervention points to prevent violence.

- Support national conflict-resolution and violence-prevention capacities, which may require choosing long-term goals over short-term gains, and adjusting expectations of “impact” accordingly. These capacities include: collective actions, coalitions, and movements that aim to empower truly grassroots actors (which are not always the same as “civil society”); and linking communities to national systems.

- Generate realistic approaches to risk management that are both acceptable to donors and better suited to conflict-affected, fragile and emerging market environments.

- Work collectively with private funders to improve coordination and understanding of how donors can best fund different levels of change and types of activities. While private philanthropists may be able to choose more effective tools to support grassroots actors, donor coalitions and partnerships are essential to tackling peacebuilding and violence prevention in a systematic manner.

- Invest in giving donors the capability to be more effective partners by:

-

Recommendations for private funders

- Prioritize funding methods that may be hard for public funders to develop, such as:

• Community-led approaches that enable local organizations to generate their own assets, thereby freeing them from ongoing cycles of restrictive grant funding. Additionally, include evaluation data demonstrating why such approaches are effective.

• Innovative finance mechanisms for peacebuilding and local organizations. Funds should be directed toward research and development examining whether the tools of a capitalist system are suitable for social change, as well as how innovative finance can be based on conflict-sensitivity analysis.

- Develop an investment matrix showing which funding tools are most appropriate to a particular operating environment.

- Explore how funders can adopt some or all of the seven strategies presented in this report for effectively funding local actors, such as participatory approaches to grantmaking, minimizing application and reporting bureaucracy, and providing only core support.

- In the case of funders already acting on the above recommendations, bring together other organizations to share experiences and promote a shifting of power from grant-givers to grantees.

- Fund people and ideas, not projects. In doing so, actively advocate for a “movement mindset” among donors in order to collectively combat global trends that run counter to human rights, peacebuilding and humanitarian work.

- Dedicate time and funds to breaking down silos, and to making clear the links between peacebuilding and human rights.

- Prioritize funding methods that may be hard for public funders to develop, such as:

-

Recommendations for local organizations

- Take the power - exercise agency and seek ways of disrupting the current power dynamic between funders and local organizations.

- Be honest with funders about the organization’s needs, the realities of implementing any required assessment frameworks, and the accomplishments their support can (and cannot) achieve. Learn to say no to funders and negotiate for better terms.

- Diversify funding – look where possible for community-led and other financing solutions, rather than relying on Western donor-funded grants as a first step.

- Seek out, learn from, and amplify the approaches of local organizations – some of which are highlighted in this report – that have managed to avoid restrictive grant funding while sustaining their work.

- Explore collaborations with other local actors aimed at designing and catalyzing new funding approaches – such as outcome funds to support an organization’s objectives or providing seed funding for a community foundation – and bring these ideas to funders.

-

General Recommendations

Understanding and Measuring Impact

- Develop and incorporate evaluation indicators that capture:

• The impact donors have on communities.

• Whether a donor’s funding has increased a community’s capacity to articulate their own needs and achieve their own goals.

- Support the development of metrics that allow for the evaluation of community-led work, and the measurement of progress related to collaborative community action.

- Measure network-building and the development of horizontal and vertical social capital, dignity, and trust.

- Research whether the efficacy of peacebuilding and development projects changes when funded through locally led grantmaking or similar strategies involving community empowerment.

Assumptions and power

- Analyze the assumptions underlying a donor’s financing. Ask:

• Who do these resources empower? Who do they disempower? How is this assessed?

• Are the people directly affected by a particular issue regarded as experts in terms of resolving it? If a grassroots issue is being addressed by an actor outside the local community, what are the assumptions behind this? What is the role of outside experts and external actors?

• How might external actors exacerbate the problem or inhibit success?

- Start a frank conversation about risk and capacity. Ask:

• Who is assuming the risk in the interventions?

• Which capacities require bolstering, and whom do they serve?

- Develop and incorporate evaluation indicators that capture:

Context

Definitions

In this report, “donor support” refers to money and other assistance from

actors external to a particular national context. As the analysis addresses challenges

related to the entire ecosystem of funding, it includes “foreign assistance” or

“foreign aid” (used interchangeably), which refers to funding from governments

or multilateral donors (the World Bank, UN, and other international or regional

organizations). Also referred to are “donor funding,” which is generally

defined as private philanthropic assistance, often provided by foundations, and

“investments,” which are funds invested by the public, philanthropic organizations,

and private businesses, with the aim of generating profit.

The Alliance for Peacebuilding defines “peacebuilding” as tackling the root causes of violence, rebuilding lives after conflict, and ensuring communities have the appropriate tools to resolve conflict without resorting to violence. Peacebuilding activities utilize a broad range of approaches, from truth and reconciliation commissions to former fighters training others in non-violent political action, to local groups mobilizing to stop violence spreading. Peacebuilding can involve “primary” or “secondary” outcomes. In the former case, this means that funding supports “traditional” peacebuilding activities such as dialogue, reconciliation, truth-telling, and memorialization. In the latter case, humanitarian relief or development activities are conducted based on rigorous conflict-sensitivity assessments that examine existing tensions (between social classes, identity or political groups, etc.). Programming approaches then seek at a minimum not to exacerbate such tensions and in some cases to build more cohesive relationships between groups. For example, UNICEF has developed an approach to programming that essentially means every intervention – from water and sanitation to reintegrating child soldiers – becomes a means of promoting peacebuilding and human rights as a primary and/or secondary outcome. [2] While humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding activities all share several core principles, such as participation and inclusivity, peacebuilding’s focus on root causes, relationships, and bottom-up efforts is unique.

This report is about “local” organizations, movements, and networks. Local is a hard concept to define as its meaning may shift depending on an individual’s perspective (for example, headquarters staff in New York or Geneva may consider country offices local, whereas country offices may consider subnational or regional staff local). In general, local is used here to denote organizations, networks, or entities (which may or may not be formally registered) led by in-country nationals responsible for determining priorities and strategy. [1]

Structure

Different readers will use the information presented here in different ways. Potential funders new to these debates and interested in innovative approaches to big global problems may gain considerable insight from the context and analysis offered in Part I. Traditional and progressive funders familiar with the challenges of donor assistance may find the greatest value in learning about new and/or effective strategies (Part II). Many may also be interested in ideas for new funding mechanisms (Part III). Local organizations whose concerns and experience are the heart of this effort may find the entire discussion useful, even cathartic.

-

To help facilitate these varied interests, the report is divided into the following sections:

- Part I: Introduction, Problem Statement, and Research Process

- Part II: Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Donors (For Supporting Local Actors)

- Part III: A New Approach to Funding Local Peacebuilders

- Part IV: Supporting evidence – Challenges

Readers should feel free to choose whichever sections speak most to their interests. The strategies referred to in Part II are those that emerged from the research. Part III, which outlines a new approach to how local peacebuilders might be funded, details original and promising means of supporting local organizations working in conflict and violence-affected settings. While not every reader may be interested specifically in innovative ways of funding peacebuilders, many of the concepts explored do have wider applicability. Finally, Part IV organizes the project’s qualitative evidence by theme, further elucidating the challenges presented by the current donor paradigm. Given the report’s priority is to contribute to solutions and effective action, a decision was taken to present these challenges at the end. Even so, the direct quotes from interviewees – funders and consultation participants - included in this section are powerful, while the analysis aims to provide all interested readers with useful insights.

Chapter Footnotes

- 1.

For a fuller description of related definitions, see: Peace Direct and the Alliance for Peacebuilding, “Local Peacebuilding: What Works And Why,” 2019.

- 2.

Metz, Z., Nilaus-Tarp, K. and Sobhani, N., “Conflict Sensitivity and Peacebuilding Programming Guide,” UNICEF, New York: NY, 2016.

Part I: Introduction, Problem Statement, and Research Process

Introduction

Violent conflict is at a 30-year high. [3] In order to address this, the international community must invest more effectively in a key and grossly underfunded lever of peace and stability – grassroots organizations and individuals working in their own communities. The author and Peace Direct have worked in partnership to explore the dynamics of, obstacles to, and opportunities for effective funding of local actors. In doing so, this report grapples with the question of how to create a meaningful shift in an industry where the same problems have been discussed for decades. We realize such a transformation will require the collective effort of a multitude of actors over many more decades. Our hope, then, is to contribute to this process by framing these problems in light of today’s sociopolitical discourses, and to offer tested but innovative solutions to the challenges that frustrate both funders and local actors. This report expands on a recent article for Alliance magazine, presenting the substance, detail, and data behind this new practical approach. Grants are the backbone of donor support to civil society organizations; however, if they are not used with great flexibility, they quickly become ineffective tools. As this report will demonstrate, there are better means of supporting social change. Some of these approaches are relatively new (innovative finance tools, such as outcome funds and social impact bonds), others less so (participatory grantmaking, community-led financing). Irrespective of age, none of them have taken hold as standard practice.

Moreover, local organizations are forced to waste resources on constant fundraising that is based on an ability to demonstrate immediate-term success. Donors must also use significant resources to monitor grants using traditional approaches and are often not reasonably able to keep up with vast piles of quarterly reports. In effect, we are using analog technology to support social change in a digital world.

This report is also a call to action – a new norm is needed, one that utilizes effective funding mechanisms for local actors. We are faced with a number of pressing and interrelated issues, from violence to climate change to migration. We would argue that anyone serious about tackling them should engage meaningfully with this report, exploring how the lessons learned about support to local efforts might be adapted to the organizational realities of different funders. Ultimately, we must address the massive gap in funding to local conflict-related actors that currently exists. One means of doing this would be through seeding a groundbreaking new fund that explores range of mechanisms to support local efforts in conflict-affected settings. Again, this is something laid out in this report.

The two quotes below from grant recipients illustrate the shortcomings of the current foreign assistance paradigm and a more effective approach. This, then, is what funding from traditional grants looks like:

Because the United States has frozen its funds to the Northern Triangle and most other donors have stopped funding peacebuilding work, it’s very hard to get money for Guatemala specifically. We should be working together but [local NGOs] are all fighting for survival and the smaller groups are dependent on us to help them get grants. We are currently managing 27 projects outside of Guatemala. From this, we try to piece together enough overhead for our primary operations in Guatemala City. We managed to pay everyone last year but this year [2019] we are facing a shortfall and will have to start firing people in December. These are highly skilled human rights experts and very hard to replace. For 25 years it’s been like this; we don’t know from year to year if we can keep our staff.

In contrast, this is what flexible funding looks like:

A private foundation was able to provide us with flexible funding that we…use[d] to create a reserve fund. We draw on this reserve fund whenever there is a lag between our need for funds and disbursements of grants from our donors (i.e. many times during each year). If we did not have this reserve fund, we would have to furlough staff and delay our activities until the funding arrived, and this of course would get us in trouble with our other donors who have given us a deadline for activities to be completed. The reserve fund has been a lifesaver for us!

As the above demonstrates, the prevailing foreign assistance paradigm has led to three interrelated problems:

- Insufficient funding for local actors.

- Funding that is inadequately structured for effective action and impact.

- An antiquated global funding paradigm that underinvests in local organizations, a key lever of social change.

Simply put, the current approaches constitute a bad business model. Devaluing local actors and perpetuating a Hunger Games-like approach to civil society funding means local efforts – which are an essential driver of social change, resilience, stability, and conflict prevention – face a huge gap in support. Such practices provoke competition rather than collaboration, undermining the billions of dollars spent in multilateral, bilateral, and private funding. Moreover, local organizations are forced to waste resources on constant fundraising that is based on an ability to demonstrate immediate-term success. These problems cry out for a new funding approach, particularly in fragile, violence and conflict-affected countries

Local actors in almost every sector – from legal empowerment to humanitarian efforts – are starved of resources. While this report refers specifically to peacebuilding actors and organizations, the issues described are systemic and applicable to “localization” overall. Many of the challenges described in this report are universal to civil society, as are the dynamics perpetuating them. [4] This speaks to the need for a fundamental paradigm shift that goes far beyond the financing of peacebuilders or justice-sector actors.

The problem

-

This research presented in this report underscores the already well-documented challenges presented by current donor and foreign assistance funding practices. These include:

- Funding that is focused on short-term projects.

- Funding that is project-specific rather than providing core support.

- Lack of responsiveness or flexibility preventing swift adaptation to changing circumstances.

- Lack of donor capacity to manage smaller grants, resulting in funding being fed through INGOs (international non-governmental organizations) and a resultant dearth of direct support for local actors.

- Administrative burdens that are too high for many local actors to overcome and are inefficient for donors.

- Prescriptive funding priorities driven by Western policy and donor imperatives.

- Aversion to risk.

- Structural biases and inaccurate assumptions regarding the capacity of local organizations.

Nanc Hann via Unsplash

Many of the above issues are framed in Part IV through the lens of assumptions and fallacies, highlighting how they have evolved into ubiquitous and enduring narratives. There are several reasons why they have persisted for so long with little change, with the belief system underlying these viewpoints foremost among them. Thus, rather than discuss the issues themselves – for which there is already ample evidence – the focus here is on how they have been perpetuated by the narratives that have grown up around them. It adds to work by Severine Autesserre and others, which is premised on the idea that naming these dynamics and providing counterexamples is a potential means of cultivating change.

This project also revealed a number of challenges not currently included in this well-documented inventory. Specifically:

- The evolution of Western donor conceptualizations of accountability and its effect on local actors.

- The consequences of the current focus on impact and how issues of measurement are understood.

- The difficulties of working within complex systems.

- The rise of right-wing and conservative ideologies which requires new strategies on the part of donors, including a focus on movement building and collective action.

Combined, these issues perpetuate the three concerns laid out below.

Three concerns

Insufficient funding

Community-level actors are facing a crisis in financing their work. Every country in the world has its share of dedicated changemakers engaged in courageous and inspiring efforts to promote human rights and end violence in their communities. Yet, as the Foundation Center’s “State of Global Giving” report reveals, of the $4.1 billion that US foundations gave overseas between 2011 and 2015, just 12% went directly to local organizations based in the country where programming occurred. [5] Meanwhile, private donors spend less than 1% of the almost $26 billion in annual global giving on peace and security writ large, including peacebuilding and prevention. Of those funds, the vast majority go to governments, international organizations (INGOs), or are fed through assessed contributions to the UN. The majority of resources focused on active conflict settings go to international humanitarian and emergency response. While this lifesaving assistance is critical, it is often no more than a Band-Aid. Humanitarian assistance is not designed to address the root causes of conflict, such as inequality, grievances, and human rights abuses. Additionally, it does not provide long-term sustainable support to local actors working in places the international community chooses to ignore or has lost interest in. Despite decades of literature and countless examples speaking to the limited utility of donor-imposed solutions to local challenges, the biases and structural barriers of the international community make such approaches difficult to dislodge. The roots of conflict are complex, and generally neither a wholly local nor wholly international response will succeed. Yet, local organizations and communities that know best how to address local problems receive only a fraction of donor resources.

Poorly structured and thus ineffective funding

Funding for local organizations is structured in such a way as to prevent them making best use of it. The challenges associated with foreign aid are well documented. Funding is overwhelmingly project based, short term, and inflexible. Donor funds – particularly government and multilateral donors, but sometimes also foundations – come attached to very high administrative burdens that many local actors cannot overcome. Furthermore, the core operating costs of non-profit organizations are chronically underfunded, hindering their effectiveness. In addition, most donor funding is prescriptive, designed to further external actors’ agendas. Calls for funding and projects are rarely designed in a participatory manner with national or community-based actors, meaning programs frequently fail to address the priorities (and utilize the solutions) that those living in recipient countries see as most salient.

Simultaneously, rather than focusing on what is actually effective, Western donors’ primary concern is often on compliance and reporting/justifying what has been done with foreign funds, a syndrome fed by the evaluation industrial complex. This prevailing paradigm is reflected in an attachment to donor control, an aversity to risk, concepts such as “capacity building,” and the imperative to “scale” interventions. Lack of donor capacity means funding is fed through INGOs that can address these concerns, which in turn results in a dearth of direct support for local actors. As one donor implored, “get[ting] more funding to these groups and places that is good quality and focused on the grassroots level, with respect for the grantee perspectives and providing core support over the long-term, trying to streamline reporting requirements so these groups have a chance at doing their real work – I can’t overstate how important this is.”

An outdated paradigm

The prevailing donor approach does not effectively support local organizations, initiatives, and networks. This paradigm is decades old, deeply ingrained and based on a fundamental power imbalance. As Edgar Vallanueva, Leah Zamore, and others have argued, it is predicated on expanding Western wealth (and philanthropy) through global economic policies and practices that exploit the resources and labor of less powerful communities, often in the Global South. These colonial approaches have privileged Western knowledge and decision-making, resulting in a lot of money being spent on short-term, donor-driven interventions, which have ultimately failed to sustainably address pressing problems such as violence.

In a broader sense, there are pernicious debates about whether foreign aid can actually help achieve its stated aim of bringing about a just and rights-respecting world built on an axiom of stability, or whether it is merely a tool for furthering donors’ agendas. Likely, this not a dichotomy – foreign aid has both furthered donors’ policy goals and been responsible for huge macro gains in the eradication of disease, as well as other interventions that have saved lives and promoted a higher standard of living. However, meaningfully addressing social justice, violence, and persistent conflict requires a different approach. The way in which donor technology, resources, and learning are leveraged is generally not through bottom-up support to local contexts – this is despite clear evidence that locally led interventions based on contextual nuances are highly effective. These issues mean assistance is structured in ways that are not well aligned to local initiatives, frustrating both donors – who know this approach is not working – and those on the receiving end of aid.

How did we get here?

Large scale foreign aid is too unwieldy for community-led intervention

Bilateral and multilateral donors provide the vast majority of foreign assistance – $144 billion in 2017. Government donors are not well situated to provide resources at the community level due to policy, administrative, security, human resource, and monitoring constraints. Nor are they well situated to provide the type of financing – core support, organizational development, and flexibility – that most organizations working in challenging operating environments need.

Public and private donors are limited by their risk-tolerance, reach, and funding approach

Conflict-affected countries do not have the stable institutions and/or infrastructure that private investors interested in social impact bonds or other social change tools are looking for. Rather, these contexts are perceived to involve a high level of risk and significant political challenges. Governments – and more likely INGO implementing partners – are often left to assume risks the private sector will not. This, however, leads to the quagmire above of government funds being a mismatch for local actors. There is a particularly salient role for private philanthropy here, which can take more risks and provide more flexible resources.

The most intractable conflicts (e.g. Syria, Yemen) are often linked to geopolitical dynamics that can seem unsolvable, making any form of intervention appear hopeless. Finding appropriate local organizations in very complex places is a huge challenge – Western donors and outsiders face prohibitions on their movements, especially beyond national capitals or major cities, and do not have the benefit of trusted local networks and knowledge. Thus, the reach of donors is usually limited and disconnected from community-based work. This means the stories of local people and communities working to prevent violence often remain unknown, particularly in the West. As one funder noted, “No one knows there is hope on the ground – the hope on the ground is often not connected to the policy process.”

In addition to the tendency to find and fund capital-based organizations, donors will usually focus on organizations with an established structure and legal status. Just as informal enterprises – for example, women selling tamales in the market – comprise a significant part of the economy in conflict-affected countries, local peacebuilders are often not part of a formal institution. This makes them both less visible and harder to fund for external donors. Donor organizations are not monolithic – while field staff may know the local scene well, including unregistered groups, they may not have the flexibility to fund them. The “theory of change” around funding local actors argues that if the world is shown that these people exist, and that they have the ability to conduct impactful and sustainable work even in dire circumstances, funders will respond with more flexible and appropriate tools.

The peacebuilding field is failing to adequately communicate why its work is both essential and lifesaving

There are some important efforts toward addressing this shortfall, including the newly launched +Peace Coalition. Part of peacebuilding’s challenge is that it has always encompassed a broad range of pursuits centered around a set of principles – such as structural transformation and eliminating root causes of violence – rather than a finite set of programs or activities. Even when the impact of their work have been clear, peacebuilders have shied away from taking “credit” for outcomes in settings where causality and attribution can be hard to establish. Conflict- and violence-affected settings are inherently complex. New studies, such as the UN-World Bank report, “Pathways for Peace,” and research by the Advanced Consortium on Cooperation, Conflict, and Complexity at Columbia University’s Earth Institute (AC4), have started proposing more dynamic and nuanced understandings of the factors driving conflict and fragility, including patterns of inequality and exclusion. Researchers at AC4 argue that in order to adequately determine the policy and programmatic intervention points necessary to sustain peace, a much better understanding of complex adaptive systems is required. [6]

The peacebuilding field needs to get better at clearly communicating its work and impact. Additionally, funding approaches need to evolve away from the silos necessitated by the development industrial complex. AC4’s research suggests that supporting local actors is one proven – and under-resourced – path.

Why is it important to solve the challenge of funding peacebuilding – and local peacebuilders – now?

The potential of peace-related philanthropy – making support for peacebuilding a core portfolio issue – in addressing major world challenges is vast. For example, conflict is a major driver of food crises globally. In 2018, 124 million individuals around the world faced crisis-level food insecurity, while 815 million suffered from chronic hunger. Of those impacted by food insecurity, 60% live in conflict-affected areas, highlighting the critical relationship between conflict and food scarcity. Peacebuilding, in addressing conflict, offers an opportunity to prevent or reduce the severity of food crises across the globe. The same is true for other forms of deprivation linked to conflict, such as forced migration, gender-based violence, and chronic underdevelopment. The UN High Commission for Refugees’ 2018 “Global Trends Report” notes an all-time high of 70.8 million people – half of them below the age of 18 – are currently forcibly displaced worldwide due to persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations. In 2018, 37,000 people were forced to flee their homes every day, with the overwhelming majority of them coming from places affected by violent conflict, such as Syria, South Sudan, Myanmar, and Venezuela. In 2017, the Jordanian government spent approximately $1.7 billion hosting 650,000 Syrian refugees. At a recent Inter-American Dialogue event, Felipe Muñoz, Advisor to the Government of Colombia on the Colombian–Venezuelan Border, noted that the cost of hosting Venezuelan refugees stands at approximately $1.3 billion per year – about 5% of Colombia’s GDP. Of course, such economic impacts don’t take into account the price of absorbing these families and individuals into communities already fraught with their own tensions and insecurities – and the risks to, for example, Colombia’s fragile peace process.

Dealing with conflict and fragility through prevention and resilience-building – rather than relying on reactive measures – is key to effective intervention. Prevention consists of activities aimed at reducing the potential drivers and root causes of violence, such as human rights abuses, inequitable distribution of land and other resources, and marginalization of communities from democratic processes. For instance, Pathways for Peace notes that targeting resources toward prevention in just four countries at high risk of conflict could save $34 billion in foreign aid budgets annually. In comparison, spending on responses to violent conflict through peacekeeping and humanitarian crisis response operations in 2016 was $8.2 billion and $22.1 billion, respectively. Increasing amounts of data make the business case for peace – for example, the Institute for Economics and Peace, in noting a $1 investment in peacebuilding programs leads to a $16 saving downstream, argues that “The total peace dividend the international community would reap if it increased peacebuilding commitments over the next ten years from 2016 is $2.94 trillion.”

In 2016, the UN adopted Security Council Resolution 2282, often referred to as the “sustaining peace” resolutions. These resolutions underscore that peacebuilding is not an intervention limited to the end of violence, but rather, as member of the Advisory Group of Experts on the Review of the Peacebuilding Architecture Gert Rosenthal stated, “…a principle that should ‘flow’ through all the UN’s engagements – before, during or after potential or real violence conflicts.” This precipitated a shift toward the principal of “sustaining peace,” a term that now prevails at the UN. These same resolutions assert that while the international community has a role to play in sustaining peace, it will only be truly sustainable when built and owned by local and national communities.

Why local peacebuilders?

The successes of local organizations working in their communities are myriad – they have negotiated ceasefires and humanitarian access in Syria, facilitated minority Tamil women’s participation in political processes in Sri Lanka, and trained youth to negotiate community water conflicts in Yemen. These individuals, communities, and organizations often consist of those best placed to prevent local violence and resolve conflict, with research demonstrating that, particularly in extremely complex operating environments, supporting local peacebuilders and civil society is frequently the most constructive path.

A 2019 report examining more than 70 external evaluations found that local peacebuilders demonstrated significant impact in: preventing, reducing, or stopping violence; improving relationships between and among people (i.e. horizontal relationships); and improving relationships between people and those governing them (i.e. vertical relationships). In terms of successfully promoting changes in knowledge and attitudes, these impacts included peaceful approaches to addressing violence; increased readiness to accept ex-fighters and refugees into communities; and better understanding and collaboration between citizens and authorities. The evaluation also evidenced significant changes in behavior, including conflicting parties participating in local dispute resolution and mediation; proactive strategies by leaders to improve cohesion; and increased citizen engagement – including voting – in non-violent democratic action. Finally, tangible structural changes were demonstrated, such as a reduction in violence in communities; greater seriousness placed on gender-based violence in courts; and more inclusive governance approaches to conflict-resolution.

The research presented in this report aligns with these findings. Investing in local capacities mitigates the risks external actors perceive they face because local people understand the context, including which actors are trustworthy and who should be avoided. As one global consultation participant noted, “Local security challenges in local communities can best be resolved by local people. Grassroot actors are part of the local communities and understand exactly why and how people do what they do. They can design local-suited solutions to it, and not what the donor thinks [are] solutions. That is why grants seem not to be solving local problems.” Funders and recipients alike noted that having local-level relationships means external actors are more aware of the dynamics and early warning signs of conflict, discrimination, and instability, with minority and marginalized groups often among those hit first by local tensions. Finally, these approaches tend to be low cost and technically appropriate, tapping into existing leadership structures and traditions.

This potential – and the aforementioned realities – lead to the conclusion that new ways of operating outside traditional Western grant-funded assistance models are needed.

Who is working on new approaches to funding local actors and what tools and strategies have they developed?

A number of important efforts are currently underway, exploring how best local actors might be supported. These include but are not limited to: research conducted by the Near Network, a movement of Global South civil society organizations dedicated to promoting more equity in development aid; a recent report by CIVICUS summarizing extensive interviews with funders and civil society organizations about how to more effectively structure funds; work by Ed Rekosh on rethinking the “human rights business model;” and various individual efforts by a range of public and private donors (with many of the latter interviewed for this report), including the newly launched Trust-based Philanthropy Project. These efforts align with many of the core messages to funders about how to maximize their effectiveness offered in this report.

The “Grand Bargain” is an agreement committing some of the largest donors and humanitarian organizations to providing additional support and funding tools to local and national humanitarian actors. Furthermore, the Peace and Security Funders Group – a network of more than 60 donors – conducted survey research in 2017 that indicated a significant number of its membership do recognize the value of funding local organizations. Despite the current “buzz” around “local,” however, such efforts tend to be siloed by sector, are disparate, and have not been scaled up. The international community has now spent decades extolling the virtues of “localization” – collectively, though, there has been little shift in practice.

In terms of adding to knowledge about how to support local actors, the research on which this report is based had two goals: 1) learn as much as possible about challenges to, and strategies for, effectively funding grassroots actors from those currently doing it; and 2) consult with local actors to assess how they envision external support being structured in order to best facilitate their work. Peace Direct is one of the very few international organizations whose mission it is to directly support local peacebuilding. This support includes mobilizing more resources, promoting local partners internationally, and advocating for a shift in policy and funding. Several members of their staff were formally interviewed for this project, while informal conversations helped shape the intellectual development its arguments. Otherwise, however, this research did not have a particular focus on interviewing funders whose core mission is to support peacebuilding (as donors specifically focused on peacebuilding are few and far between). The implicit question arising from this was how to address this gap in funding, and whether it might best be done through a new funding mechanism. The snowball sample included 25 funders (see Annex) working on a variety of issues, including climate change, HIV/AIDS, education, child protection, human rights, blockchain and social finance. The “demand” side of donor funds were also consulted about their needs through a three-day online consultation with civil society, local actors, and individuals working on funding issues across every continent.

Chapter Footnotes

- 3.

UCDP, “The UCDP/PRIO (Uppsala Conflict Data Program/Peace Research Institute Oslo) Armed Conflict Dataset 2017,” 2017.

- 4.

This is borne out, for instance, in “The Human Rights Documentation Toolkit,” a resource designed to assist grassroots documenters and civil society organizations working across a range of thematic issues (transitional justice, child rights, forced migration, land rights, women’s rights). Published in 2016, it utilized survey data related to the self-reported challenges of 55 organizations in 42 countries. The most frequent responses concerned security concerns (of staff, information, interlocutors); lack of infrastructure and/or monetary resources; and lack of human resources.

- 5.

The other 88% passed through intermediaries: INGOs or spent operationally by grantees based in the Global North; US public charities re-granting funds to local organizations; organizations indigenous to their geographic region but working across countries; multi-lateral organizations that work on a global level (e.g. the World Health Organization); and research institutions conducting research in different countries where they are headquartered (The Global Giving Report, p.11).

- 6.

Coleman, P. et al., “The Science of Sustaining Peace: Ten Preliminary Lessons from the Human Peace Project,” New York: Columbia University, unpublished conference paper.

Part II: Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Donors (for Supporting Local Actors)

The approaches below emerged from the interviews as best practices. While they may be known to a certain subset of funders, these principles are far from the norm and therefore bear repeating:

STRATEGY ONE: Implement innovative and participatory approaches to funding, program design, and evaluation

Several funders in this project have focused on participatory philanthropy approaches. This set of principles attempts to shift the balance of power by asking questions such as: Who decides how funding resources are allocated? Who participates? And who decides who gets to be at the table in such discussions?

It was noted that this can be a very important approach in divided and conflict-affected societies, with one funder explaining, “[These methodologies] involve getting a range of input related to different political/identity groups or whatever may have fueled the conflict – and also include different actors traditionally outside the peacebuilding field, like economic actors.

The challenge is this is time consuming. It requires very good facilitation and understanding of local politics and context, though this is a potential contribution of peacebuilding because we have a few decades of well-trained facilitators.”

Supporting collaboration

One funder encourages partners to work together by supporting clusters (connected by networks, project-specific issues, or geographic area). This, the funder feels, is more impactful and decreases transactional costs. Another funder reported they don’t have one single approach: “How this looks and what types of resources you provide vary from place to place and need to have some strategy. In a place like Nigeria, which is huge, you can’t give 20 grants all over the place and expect to learn some sort of larger lesson about impact.”

Innovative finance

In general, innovative finance – an approach discussed in greater detail in Part III – refers to any tool outside of traditional grants, and can include impact investing (generating both financial and social return); blended finance (the use of public funds to mobilize private investment leveraged toward social outcomes); bonds and outcome-based financing; cause marketing and corporate partnerships; and various forms of social entrepreneurship. One funder noted that these mechanisms are often “structured right now in the way that banks do it. Practicing impact investing in a way that serves local organizations and partners would look different.” For example, Thousand Currents started the Buen Vivir Fund – an impact investing fund they spent one-and-a-half years setting up through work with partners across the world: “We went through a long, thoughtful planning process with numerous stakeholders and came up with a new mechanism that reflects the values that local organizations thought were important (e.g. some of the indicators are happiness or joyfulness)…It was a heavy lift, just adopting the concepts and then we did a lot of work with a team of US-based lawyers and tried to find lawyers in the different countries in which the loans operate to figure out how to create LLCs in other places.”

Locally owned philanthropy

There are an increasing number of locally led philanthropic efforts and related movements, including the European Community Foundation Initiative and the Global Fund for Community Foundations (GFCF). The latter aims to support people-building capacity and social capital in communities in the Global South. As the Executive Director described it, this is a movement about “…funders within the community rather than to the community.” She further noted, “Which grantmaker talks about social networks or capital? Things that are hard to measure. The community foundation movement relates to [building these capacities and] truly empowering the most marginalized. If the women in a community all gave $1, maybe that adds up to $50 – it’s not big bucks, but how do you measure/value that if you understand it as an attitudinal change, an investment in your community and the future of your children. We believe ‘No one is too poor to give or too rich to receive.’”

When Tewa (the Nepal Women’s Fund) – one of the Global Fund for Community Foundation’s partners – makes grants, they also ask partners if they want to give back to the fund. In this way, the power paradigm is flattened: “By giving back, you are not just a recipient but also a donor.” Effectively, the question they are asking is: How does it change the story of funding if you start to change the terms of the conversation? GFCF’s Executive Director went on to note: “Take the Dalit Community Foundation – the mere existence of this organization, this is a subversive act. We have been told we are a community and [this type of philanthropic community organizing] lets us embrace that as a source of power rather than as the most marginalized in our society.” [7]

Regardless of approach, interviewees stressed the need to test out different ways of getting funds to the grassroots level. For example, Peace Direct’s Local Action Fund – an atrocity prevention program in Myanmar and Nigeria – aims to reach local-level initiatives through a combination of microgrants to community-level grassroots initiatives and small grants to civil society organizations. The fund aims to be as flexible and responsive as possible, taking cues from communities and civil society groups about what works, and considering applications on an ongoing, rolling basis. Meanwhile, Spark Microgrants funds “hyperlocal organizations,” which are more like collectives. They are often not formal organizations at the outset of the community grant process but become formalized over time. Spark Microgrants noted that their American-led partners have considerably more access to funding: “Organizations that are actually from these local communities have a really hard time accessing funds, and the funding that is available is within a project and prescriptive model.” It is worth imagining, then, what the impact of creating a significant pool of funds available to hyperlocal groups would be, particularly if the groups were accountable to a set of established standards they helped co-create?

STRATEGY TWO: Shift from transactional to relational partnerships

As one funder noted, “The nature of donor–grantee relationships is usually transactional – money from one side and extractive knowledge from the other. These are not the type of long-term partnerships that are conducive to the kinds of impacts the international community is supposedly seeking.”

Certainly, authentic and effective donor–grantee partnerships exist. Across the board, as shown by this and other research conducted by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors and the Social Change Initiative, donors and recipients noted their partnerships were most effective when their convening authority was focused on creating “spaces” and networks, with trusting relationships built up through working with partners to get them the resources they need. Such resources could take the form of operational or program support, technical assistance, access to international fora, or solidarity in difficult and often heartbreaking work. As one funder noted, “The difference between being [a big international donor] and a women’s fund in Serbia is that the women’s fund has to live with its decisions. There needs to be a lot of support for people at this level. This is not always forthcoming – people are so focused on program delivery that they aren’t thinking about partnership and how to support those on the ground.” A survey of 125 local peacebuilders from all regions of the world, reiterated by global consultation participations, indicated their topmost request for support from the international community was greater recognition of the importance and impact of locally led efforts. Funding came in ranked as the fourth priority.

Donors and grantees overwhelmingly emphasized the importance of facilitative relationships. As one funder put it: “Part of an effective funders’ job is really getting to know [partners] so we can help identify how to support their work in a constructive and comprehensive way.” This can involve providing technical expertise when partners request it (for instance regarding financial management or security training; or training on new laws and policies – such as sanctions or money-laundering – that increase fiscal or due diligence processes). Relational support can also take the form of facilitating national, regional, and international connections and learning exchanges: “Organizations often want to meet with grassroots organizations, networks, and movements in the US, less so with governments. They are interested in peer-to-peer learning, what are they doing around their issues? How are they working towards social justice? Are there common approaches or tools?” Other strategies include amplifying local organizations’ campaigns and stories, and helping to find other funders. Some donors spend a lot of time in convenings and conference spaces, getting to know other donors, in order that they are well positioned to make these types of connections. The key element in all these approaches is trust. As one funder noted, “The bottom line is we trust our partners. We trust their wisdom, their judgement, and their assessment of what their community needs.”

One funder spoke of the importance of ongoing, probing conversations when attempting to understand and address the real needs of partners: “A lot of times when we ask what types of support they need, they say training or capacity building – they may certainly need that in some ways, but we also find that’s an easy language that’s been imposed by the international community – easy to fund, easy to monitor, easy to count. When we work through it with them, we often end up talking about what they are doing after the capacity building – what are they then doing with the capacitated individuals! This is more strategic vision, building campaigns and leadership – other types of partnership support that we can offer.”

Additional strategies to support partners (which often emerged from their requests) included:

- Keeping in touch beyond the lifecycle of a project and letting partners know about new opportunities.

- Nominating organizations for prestigious prizes, such as the Goldman Environmental Prize.

- Accompanying partners on global speaking tours.

- Facilitating connections with policymakers and other influencers: “Funders can be quite useful because they can open doors, governments are more willing to meet with funders than local groups, they can often have significant convening authority.”

- Influencing philanthropy by convening discussions, bringing partners to speak at key fora about effective funding strategies, developing training and educational opportunities for philanthropists, and writing opinion pieces and op-eds: “We cannot just be a ‘typical donor’ giving away money. Being based in the US comes with access to the philanthropy sector and so part of the responsibility of funders is to change how donors operate. Despite so many decades of discussions, to give resources in a less burdensome way.”

STRATEGY THREE: Focus on systems-level issues

From health care to human rights, funders noted that programming tends to focus in on the provision of services rather than considering how these programs link to wider systems. As one funder commented, “Easy to fund, easy to measure,” to which might also be added, profitable to evaluate. Yet, one productive role the international community can play is maintaining a focus on the “forest through the trees”– that is, holding a bigger systems perspective which implementers on the ground can find very hard to address given their focus on the immediate needs of their communities. It was suggested that international foundations could assist in this by providing more strategic analysis on how to affect systems, as opposed to the current, excessive focus on service delivery.

For example, a global foundation with country offices noted that the latter are challenging HQ in a productive way to think more about how, at the country level, their programming includes an explicit, strategic focus on the integration between service delivery and systems change. This is particularly salient when considering the prevention of violence and promotion of resilience, which requires more focus on underlying systems change, in concert with direct programming strategies.

STRATEGY FOUR: Prioritize local knowledge and expertise

The international community’s refrain about needing to “understand local contexts” is ubiquitous. Regardless of the sincerity or otherwise of this assertion, a deeper shift is required, one that acknowledges that the real experts are country nationals. External actors will always be learners, and may never fully understand the complexities of a particular setting. Though there are plenty of external actors dedicated to making the work of their organizations reflect this principle, as a system this is not reflected in the policies and procedures of donor assistance.

Today’s risk-averse and security-constrained environment makes getting out of capital cities difficult for external donors. This is particularly the case for governments, which face greater restrictions. The result is that the relationships and information upon which decisions are made are often constrained. One funder underscored that finding truly local initiatives is a huge job, requiring considerable time and resources:

"[The international community] hasn’t done a good job of finding and investing in [local] people – we need to think about how we even find people to fund, what are the biases in this process. This is where we need networks of local experts to help us understand the context. As an organization, we spend a lot of time finding them, a lot of time talking to them and a lot of time trying to understand the ecosystem in their context and map the actors. Who are the “briefcase NGOs?” Those organizations that essentially syphon off - instead of adding to - local resources. We then help these organizations chart their path – we don’t determine what they do."

Private funders emphasized multiple strategies, including hiring program officers from the regions in question, as well as frequent travel to places where funding is ongoing.

Recent evaluation research sounds a note of caution regarding the trend toward Northern NGO “localization” in the Global South, suggesting that while it holds numerous benefits for international NGOs, it has not resulted in the systemic investment in domestic priorities and cultivation of national constituencies for human rights that lead to long-term change. Indeed, in terms of understanding local contexts, connecting local actors to systems, and building the relationships donors claim are necessary for meaningful support, many funders stated there is no substitute for national country directors and staff in leadership roles from the recipient region. As one interviewee commented:

It’s hard to get reliable info in these places. It’s really important to know what is going on behind the scenes, with social movements, the government, relationships between organizations and communities…many organizations are very adept at writing proposals and reports, have media access and you can think it’s having an impact, but when you go to the field you learn about the programming in a different way…there is no substitute for deep knowledge of networks, trusting relationships, and really understanding what the work is. In addition, there is a bias in what partners often tell funders – the totally honest assessment of what is helpful, what any timebound amount of funding is likely to accomplish, is rare. Being very close to the ground is very important – we have developed a relationship of trust with these partners over years. This helps us in the current landscape with draconian NGO laws and other repressive developments.

Some private funders may balk at creating more offices and hiring more staff, thereby increasing overheads and reducing the amount of grant money available to local organizations – such choices about organizational structure have legitimate pros and cons. Generally, however, more consideration needs to be given to meaningfully understanding and supporting domestic priorities.

STRATEGY FIVE: Shift the burden to funders

Another successful set of practices involves shifting administrative and due diligence burdens onto donors’ shoulders, thereby freeing up partners to do their programmatic and other work. Some funders ask potential partners to submit existing organizational documents, such as annual work plans and budgets, rather than requiring new project proposals or burdensome reporting requirements. One funder simply asks once a year, “What do you want to share with us?”

Many of these funders do not put out “open calls” for funding, in which they essentially advertise they are seeking partners working on a specific set of issues. Such calls usually require fairly extensive proposal packages – a recent process for a government donor stipulated 14 mandatory attachments in addition to the requisite ten-page project narrative. Not only are these processes labor intensive, they mean offering intellectual property that some funders then incorporate into their approach. This work is rarely compensated – of course, part of the point of competition is that there is no guaranteed payoff. Funders that do not put out open calls have been critiqued for putting in place a system that leads to a narrow set of partners they already know. However, these funders have responded by pointing out that the supposed “level playing field” created by open calls is a farce due to the ways in which donors prioritize applicants. Funders noted that finding partners and developing relationships is a very resource-intensive process, with one interviewee explaining, “We never funded anything based on paper applications but rather in-person meetings whenever possible with the group in their context. We put a lot of resources into having an informed local circle of influence and a local structure that makes decisions based on triangulation of information and trust and accountability borne from operating in that particular context – in this way we try to avoid gatekeepers.” Another funder described the process as follows:

We don’t have open calls. We decide on several priority areas in collaboration with a set of local partners and look for organizations that approach these issues holistically. We do a lot of groundwork up front and generate a list of potential grantees and then meet with them in-country – we don’t make partners fill out long applications, we do the work of vetting potential partners. We then invite them to be the recipient of a catalyst grant where we work together for a year – a small grant that, like all of our grants, involves comprehensive, flexible support. After that, we decide together if it makes sense to continue the relationship.

This approach of reducing paperwork of questionable utility explicitly challenges the assumptions and fallacies discussed in Part IV. As one funder observed, “We don’t believe the concept that more extensive reporting equals better due diligence and accountability. We believe in leveraging local networks to do due diligence and we assume the burden of monitoring this through relationships and regular conversations. Accountability is inherent because these people, networks, and organizations have deep relationships in their communities.” Similarly, another interviewee explained, “As a funder, even if you are giving away small amounts of money, you are validating certain actors and that has an important symbolism – if you validate the wrong group, you are in trouble [as an external actor]. This is mitigated by spending the time to develop deep relationships and contextual knowledge, not by paperwork.”

STRATEGY SIX: Provide support to movements and collective action

Some interviewees talked about the need for funders to take a strategic approach to the way democracy itself is being undermined in many countries, and perhaps globally. To this end, one funder specifically invests in a three-pronged approach: 1) supporting social movements and actors that counterbalance this trend;

2) engaging with local and national authorities to ensure that the government works in the interests of its citizens;

and 3) pushing for accountability and justice in countries that have suffered mass violence.

This funder is putting particular effort into developing tools to assess the strength of movements – examining their leadership, strategies, and development. These tools explore such questions as whether a movement has a strong base but struggles to put a strategy together. This information helps them think about where, as a funder, their support might best be employed going forward.

Supporting social movements and building networks of NGOs may require different approaches; indeed, another funder discussed their explicit strategies regarding funding the latter. These involved providing resources for convening networks and, as mentioned above, evaluating their density and therefore strength. The respondent noted, “There is a reality that building these relationships – especially across geographies – involves concerted work; these networks need to be nurtured over time and sometimes that is a capacity issue for funders. However, this is a key function of funders – to prioritize support to convenings or other fora that enable people to get together and share and build relationships.”

STRATEGY SEVEN: Emphasize longer-term and flexible funding

The need for long-term flexible funding is a drum beat familiar to most funders and funding partners. Program flexibility and financial due diligence – both important issues, especially in areas of conflict where associated levels of corruption are often high – are intertwined to some degree, and would benefit from explicit strategies centered on flexibility. Below, rather than reiterating this clear need, the discussion aims to shed light on why current practices are hard to shift, and how in some cases funders have managed to achieve change. An influential group of funders – including NoVo, Thousand Currents, and Humanity United – have committed to changing short-term, inflexible practices and their approach needs to be expanded. The likely starting point for this would be gathering evidence on why long-term and flexible support are more effective approaches.

Longer time horizons

As one funder noted, “If the mission is about social transformation, organizations need support that can span a range of time horizons and be used flexibly.” There are funders that provide support with a longer-term time horizon – the NoVo Foundation, for instance, has committed to seven years of core support. Thousand Currents started with three years of support, then when they realized this was insufficient, agreed to provide another three years. They then extended funding to ten years before eliminating timebound grants altogether: “…then we said, ‘Why are we attaching time-frames to this? It takes how long it takes.’”

Many funders noted that despite decades of discussion about how such policies are the way forward, not a lot has actually changed. When asked why this is the case, answers included: “inertia from these processes;” “the development industrial complex that focuses on hard skills, projects, and measurable outcomes which need to be accomplished in certain time-frames;” and the fact that economic, social, cultural and political rights issues are often subject to the same expectations applied to agricultural development and water and sanitation issues, despite the vastly different processes and time horizons involved.

“Radical flexibility” – with just enough structure